by Teresa Genaro

For thirty years and more there was hardly a great race run in which one of their horses did not figure conspicuously. They were a city-bred pair, but they possessed an instinctive knowledge of horses and a talent for management that made them formidable from the beginning of their career.

William H.P. Robertson, The History of Thoroughbred Racing in America

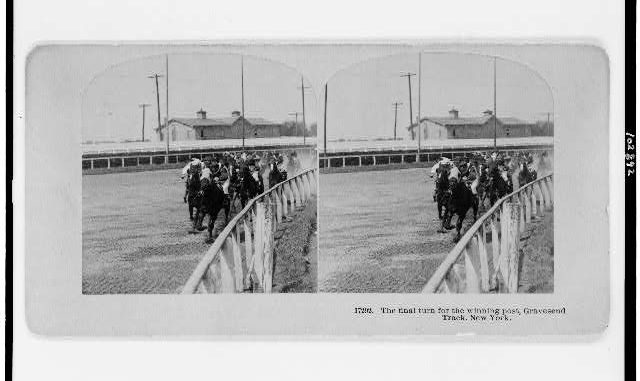

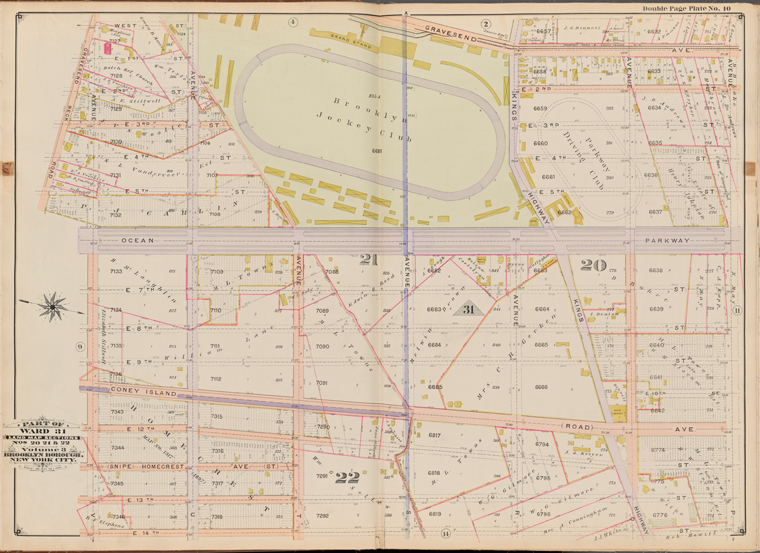

They were Brooklyn boys through and through, the Dwyer brothers; they lived in the borough in what is now known as Park Slope, and their butcher shop was at the corner of Atlantic Avenue and Court St., then as now, the heart of downtown Brooklyn. And the track that they helped bring into existence, Gravesend, was one of three in Brooklyn in the late 19th century.

It was that butcher shop that got them into horse racing. According to a February 1950 article in the Milwaukee Sentinel, August Belmont was one of their customers, and one day, he offered to sell them a horse. Her name was Rhadamanthus, and soon Phil and Mike Dwyer’s specialty became not selling cuts of beef, but purchasing horses with a proven record on the track, horses that would remunerate them with purse money, but as importantly, particularly in Mike’s case, with gambling winnings.

The Dwyer brothers were spectacularly successful in their three decades in racing. As partners or on their own, they won the Kentucky Derby twice, the Preakness, the Belmont five times (in six years 1883-1888), and the Travers five times in a decade. Their horses included Hindoo, Kingston, Hanover, Miss Woodford and Luke Blackburn, who raced at Saratoga seven times during the 1880 meeting. A lengthy 1881 article in the Times detailed their racing prospects and successes, noting that they “have always been opposed to paying great prices for horses, but departed from their principles when they purchased Hindoo…”

Like all brothers, Phil and Mike didn’t always get along, and despite all their success, their different approaches to their business led ultimately to a dissolution of their partnership in 1890, an occurrence that merited its own coverage in the Times, which noted that the brothers were “above all…perfectly honest, and are favorites with the betting public, because every one knew he would get a run for his money with the Dwyer horses. That both are to continue on the turf is a good thing for the best interests of racing.”

They both did continue on the turf, but as their paths diverged, so did their fortunes. Mike brought a string of horses to England, an endeavor characterized by the Daily Racing Form as “disastrous,” one that led to a physical and emotional breakdown and an utter reversal of his earlier fortunes.

Phil, the more conservative of the two, continued to amass wealth and outlived his brother by seven years, dying, according to contemporary accounts, later, richer, and happier than his younger brother.

A 1900 article titled “Famous Turf Plungers” had ranked Mike among the nation’s most well-known gamblers, and his obituary in the Daily Racing Form carried the admirably alliterative but pathos-packed sub-head “Once Famous Plunger Passes His Last Days as a Practically Penniless Paralytic;” the Times called him “perhaps the greatest plunger the race track ever knew” and offered painful details about the end of Dwyer’s life.

His fortune gone, his best horses stripped from him, and the means of indulging his passion beyond his reach, the inevitable reaction came. He suffered a nervous collapse, and, shattered in body and mind, unable to move without assistance, articulating with difficulty, death slowly creeping upon him, he became the pitiable, pathetic figure that racing men watched with veneration and awe at the race tracks.

He was the old plunger gone broke; the racing star relegated to the limbo of the paddock; a counterpart of the decayed speculator who haunts Wall Street and the scenes of his former greatness, and amid the shouting of the men on the Exchange lives over the events that wrecked his life, just as Dwyer, when the cloud of dust up the stretch, the gleam of red, gold, scarlet, and pink, and the swelling roar in the stands foretold the finish of a race, dreamed of the old days when the click of the stop-watch was necessary to decide whether he had won or lost a fortune.

The Form said that Mike “to the last retained the respect and liking of those who had known him in the days when the name Dwyer Brothers was synonymous with the most exalted success on the turf.” He was 60 years old when he died in his Brooklyn home on Gravesend Avenue.

Phil lived until 1917, and though his involvement in racing diminished after he split from his brother, he never abandoned the game that had brought him fame and fortune. At the time of his death, he was the president of the Queens County Jockey Club (which founded Aqueduct Racetrack), and the Times attributed his death to “his devotion to the sport of kings,” saying that he’d attended opening day at Belmont Park on a damp, chilly day to see the Metropolitan Handicap. He caught a cold that became pneumonia, and he died on June 9, the day of the 31st running of the Suburban Handicap:

At 4:29 1/5 P.M., A.K. Macomber’s Boots went under the wire a winner from Borrow and the Finn, and at exactly 4:30 the nurse reported to relatives in attendance that Mr. Dwyer was dead. It was the first renewal of the Suburban he had missed.

The news of his death was telephoned to Belmont Park. (Robertson)

Michael Dwyer, said the Times, “paralyzed the betting ring with the magnitude of his wagers.” Philip, it said, was “content to race horses for the sport.”

Quoting an unidentified source, Robertson called them “brothers from the other side of the tracks, and from across the river as well.” Butchers by trade, they are among the most influential men in the history of New York racing; the sport as we know it here would likely not exist without them.

And so, in 1918, the year after Phil died, the boys from Brooklyn were immortalized in a race named for their home borough, and run for 23 years at Brooklyn’s Gravesend track, the track that they had founded, when the Brooklyn Derby, fittingly, became the Dwyer.

Quoted and consulted

“A String of Fast Horses,” New York Times, March 21, 1881

“The Dwyers To Separate,” New York Times, August 19, 1890

“Famous Turf Plungers,” New York Times, June 24, 1900

“M.F. Dwyer, Plunger, Dead At Gravesend,” New York Times, August 20, 1906

“Michael Dwyer Dies At Brooklyn Home,” Daily Racing Form, August 21, 1906

“Phil Dwyer Is Dead,” Daily Racing Form, June 12, 1917

“Phil Dwyer Dies As Suburban is Ended,” New York Times, June 10, 1917

“Unlucky Plunger,” Horace Wade and Irving Johnson, Milwaukee Sentinel, February 12, 1950.

Robertson, William H.P. The History of Thoroughbred Racing in America. Bonanza Books, 1964.

“Brooklyn Once Had Big-Time Horse Racing, Too,” New York Times, July 21, 1963

Hotaling, Edward. They’re Off! Horse Racing at Saratoga. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995.